On Monday 22nd June, 2015, I had the pleasure of taking part in The Durham Centre for Humanities Innovation (CHI – pronounced like Thi-Chi) workshop looking at The Emerging Humanities: Strategies for the Future. The aim of the workshop was to explore the Institute for Advanced Study theme of Emergence, as applied to the emergence of new ideas, approaches and disciplinary trends in the humanities. It was a great day with lots of stimulating discussions, a big thanks to all of the organisers.

On Monday 22nd June, 2015, I had the pleasure of taking part in The Durham Centre for Humanities Innovation (CHI – pronounced like Thi-Chi) workshop looking at The Emerging Humanities: Strategies for the Future. The aim of the workshop was to explore the Institute for Advanced Study theme of Emergence, as applied to the emergence of new ideas, approaches and disciplinary trends in the humanities. It was a great day with lots of stimulating discussions, a big thanks to all of the organisers.

During my talk, I took the opportunity to think about the possibilities of taking digital humanities research outside universities and into cultural heritage organisations.

As it turns out my talk was quite lively, and in fact quite different to many of the presentations during the workshop. So I thought I would include the slides and my notes to act as an explanation – the notes themselves might not accurately reflect the exact words spoken – once I’m on a roll lots of thoughts come tumbling out.

I was initially inspired by Sheila A. Brennan’s blog post DH Centered in Museums? which discussed her lecture at John Nicholas Brown Public Humanities Center. The Lecture focused on the brilliant idea that Digital Humanities centres might benefit from moving into a museum setting. Of course! Why hasn’t anyone done that yet!? (and if it has been done – can you let me know where? Because I want to visit!) This also follows on from Neal Stimler’s panel discussion in Atlanta in 2011 at the Museums Computer Network about the future of digital humanities in museums, which I was lucky enough to attend. There are some excellent video contributions as part of this panel over on YouTube.

I also pinched the slide design from the DH2015 poster – I thought it would be good to have a digital humanities colour scheme to support my points. I hope nobody minds!

Taking the idea of taking Digital Humanities out of universities as a starting point led me to think about how we can create new spaces of innovation and experimentation and how digital humanities could be used as a starting point for thinking about the future of humanities communication and public engagement.

Why did I start a talk around the future of humanities with a slide about science communication?

Well… There is a strong history and active research practice surrounding science communication but this if often lacking in the arts and humanities research. I think we can learn a lot from science communication.

Science communication generally refers to public communication presenting science-related topics to non-experts. Essentially it’s about communicating scientific outputs of research in an engaging way. This often involves professional scientists, but has also evolved into a professional field in its own right. The art of science communication is to pitch something traditionally perceived as complicated in a way that is not only engaging but also faithful to the evidence. In essence making science accessible, engaging and exciting to non-scientists.

A definition of Science communication that I really like is one with all the Vowels! It is one of the most representative definitions of Science Communication. The AEIOU definition of science communication by Burns, O’Connor, and Stocklmayer. (2003). This looks at the use of appropriate skills, media, activities, and dialogue to produce one or more of the personal responses to science (the vowel analogy). Personally, I think that the five components of the AEIOU approach is a good way of thinking through a process of active participation in not only science communication but Humanities communication.

The SciCom definition was to provide a bit of context before getting on to an issue within the humanities. The ‘Public’ cares about the humanities…But they don’t necessarily care (care is probably a strong word – so lets change that to understand) understand as much about the work of academic humanists.

Firstly – what do I mean by the ‘Public’? Thinking of the public as an undifferentiated whole is unlikely to help develop any kind of purposeful, responsive and respectful engagement. The definition of ‘public’ developed from that provided by HEFCE:

”The ‘public’ includes individuals and groups who do not currently have a formal relationship with an higher education institution (HEI) through teaching, research or knowledge transfer.”

There are differences between individuals (including their backgrounds, interests, economic circumstances, gender, sexuality etc ) which shape their own sense of themselves and their agency.

How can our work be interesting useful and meaningful to the ‘public’?

How can our work be interesting useful and meaningful to the ‘public’?

There are multiple ways. There is huge potential to develop new ways of working to enhance access and awareness, engagement and enjoyment, creativity and interest in Arts & Humanities research.

At the workshop I discussed one potential way digital humanities can be used to change our relationship with the public.

So I asked can digital humanities be a conduit between the public and the academy? Or can it be a new kind of multivocal conversation that the public can join?

Before you can answer those questions, it was necessary to lay the ground work on what Digital humanities actually is…

Over the past 20 years or so, the field we now refer to as digital humanities has been known by many terms: humanities computing, Humanist informatics, literary and linguistic computing and digital resources in the humanities to name a few. Most recently it has predominately been known as digital humanities.

But what is it in the first place?

Is it an amorphous field that had become a catch-all for anyone doing anything remotely “digi-savvy” in the Humanities? The question of what is DH seems to be repeatedly asked, but seldom answered to anyone’s satisfaction. It may even be that the act of asking is, in itself, what some scholars think digital humanities are about.

To me it’s a very loose confederation of researchers that are engaged in A&H research, from different disciplines and sectors. It is a Community of practice. Researchers who are using digital in various ways to raise and address new questions exploring how we can apply technology to our experience of the arts, humanities, culture, & heritage. DH questions how technology changes the environment around us, physical and digital, and discusses whether those changes are for the better.

The focus of my talk was a discussion of alternate futures of digital humanities outside of the university. So, I thought I would take the opportunity to think about the possibilities of taking digital humanities research outside universities and into cultural heritage organisations. And I wanted to discuss with the group, if being more connected, engaged, interdisciplinary and innovative makes sense, if it is actually practical, or if we all just need to collaborate more.

The focus of my talk was a discussion of alternate futures of digital humanities outside of the university. So, I thought I would take the opportunity to think about the possibilities of taking digital humanities research outside universities and into cultural heritage organisations. And I wanted to discuss with the group, if being more connected, engaged, interdisciplinary and innovative makes sense, if it is actually practical, or if we all just need to collaborate more.

I often think that potentially the future of humanities research is not within the traditional constrains of academia, but is an open, collaboration between the cultural sector and academics in public space. Enabling the exploration of the importance and benefits of cross-sector and public collaboration and engagement.

So, can cultural heritage practice foster public engagement and greater collaboration amongst researchers and the public? We are now being asked more and more to demonstrate our social impact. So can working with and learning from museum, library and archive practice provide opportunities for researchers to work collaboratively, become more open and transparent to show the relevance of their research to society?

But rather than the title of the talk Taking Digital Humanities Outside of Academia – what if it is already out there?

So Interestingly DH happens in cultural heritage organisations, but just isn’t called that.

“Digital humanities” is a very academic term, and is irrelevant to some. This raises issues around if we need to define Digital Humanities? Should we just get on with the doing rather than getting bogged down in definitions that are limiting. Thinking broadly helps to think of multiple roots to Digital Humanities projects and to its multiple futures.

First, let’s look at DH that is already happening in museums: I’m going to highlight a couple of examples of interesting digital humanities projects:

The Cleveland Museum of Art’s Gallery One. Gallery One is transforming how museums can incorporate visitors’ active participation in gallery spaces. It opened to tremendous acclaim and fanfare with a range of digital interactives throughout the gallery space offering opportunities for visitors to participate.

The Cleveland Museum of Art’s Gallery One. Gallery One is transforming how museums can incorporate visitors’ active participation in gallery spaces. It opened to tremendous acclaim and fanfare with a range of digital interactives throughout the gallery space offering opportunities for visitors to participate.

The image is of the Collection Wall – it is one of the largest multi-touch screen in the US—a 40-foot, interactive, microtile wall featuring over 4,100 works of art from the permanent collection (most of which are on view in the galleries). It’s purpose is to facilitate discovery and dialogue with other visitors and can to act as an orientation experience, allowing visitors to download existing tours or create their own tours to take out into the galleries on iPads and mobiles. The Collection Wall enables each visitor to connect with objects in the collection in a playful and original way, making their visit a more powerful personal meaningful experience. Gallery One is, to date, the only non-science gallery which main focus is to use innovative technology to shift the visitor experience to emphasise engagement, curiosity and creativity.

The scale of public participation in crowdsourcing projects is impressively large. The Zooniverse projects have more than 800,000 registered users, (www.zooniverse.org). A nice humanities example is Old Weather a collaboration between Zooniverse and The National Maritime Museum.

Where users transcribe historical ships’ logs. These transcriptions contribute to climate model projections and will improve our knowledge of past environmental conditions. Old Weather project transcribed over a million pages from thousands of Royal Navy logs in less than two years.

Museums obviously focus around visual and object collections and are very good at connecting and visulizing that data. For example colour lens visualizes multiple collections by colour. It makes use of Public Domain images from the Rijksmuseum, the Walters Art Museum (Balitmore), and others with permission from the Wolfsonian-FIU (Miami), and was developed using code from Tate and the Cooper-Hewitt Museum.

Museums obviously focus around visual and object collections and are very good at connecting and visulizing that data. For example colour lens visualizes multiple collections by colour. It makes use of Public Domain images from the Rijksmuseum, the Walters Art Museum (Balitmore), and others with permission from the Wolfsonian-FIU (Miami), and was developed using code from Tate and the Cooper-Hewitt Museum.

Highlighting that once digitised collections are available via an API (application program interface – a set of routines, protocols, and tools for building software applications), they can be used them and put them into context with other objects.

Moving on to Libraries:

The British Library’s Georeferencer project is crowdsourcing location data to make a selection of its vast collections of historical maps fully searchable and viewable and comparable to modern maps.

The British Library’s Georeferencer project is crowdsourcing location data to make a selection of its vast collections of historical maps fully searchable and viewable and comparable to modern maps.

So far they have georeferenced 50213 Maps within 17th, 18th, and 19th-century Books. (they have just added a further 50,000 more digitised maps to be georeferenced).

Trove, which crowdsources annotations and corrections to scanned newspaper text in the collections of the National Library of Australia, has around 75,000 users who have produced nearly over 130 million transcription corrections since 2008.

Paul Hagon from Trove estimated that if they had to employ staff it would have cost in the vicinity of $12 million.

and Archives:

I’m cheating a bit here because I’m talking about special collections within a university with this one.

I’m cheating a bit here because I’m talking about special collections within a university with this one.

The archive of Bloodaxe Books, newly acquired by Newcastle University, is one of the most extensive and significant poetry archives in the world.

The aim was to be more creative, open-ended and playful with the archive. Designing new digital interfaces which enable new ways to explore and think about poetry.

These interactions are made possible through reframing the traditional idea of an archive, by questioning the notion of search as simply objective and designing new kinds of playful participatory interfaces with archive material.

The Great Parchment book held in the London Metropolitan Archive, is a crucial historical text documenting the City of London’s role in 17th century Ulster that was previously unreadable for over 200 years due to fire damage.

The Great Parchment book held in the London Metropolitan Archive, is a crucial historical text documenting the City of London’s role in 17th century Ulster that was previously unreadable for over 200 years due to fire damage.

The manuscript consisted of 165 separate parchment pages, all of which suffered damage in the fire in 1786. The uneven shrinkage and distortion caused by fire had rendered much of the text illegible.

The project was a large collaborative undertaking in which the practical conservation of the Great Parchment Book was the essential first step, followed by the digital imaging and flattening work. After that, the aim was to develop a readable and exploitable version of the text, comprising a searchable transcription and glossary of the manuscript. The ultimate goal of the project was to publish both the images and transcript online.

So what can we learn from the cultural heritage sector and from digital humanities projects about future directions of humanities research?

So what can we learn from the cultural heritage sector and from digital humanities projects about future directions of humanities research?

I should probably say at this point that I am interested in this from two sides – for over ten years I have worked in and around museums on a range of digital projects, and for the past 5 years I have been an academic digital humanist. My background in these two fields have shaped my perspective massively. I strongly feel that important things can be learnt from working with cultural heritage sectors – particularly that surprising research findings and/ or ideas for future research can emerge from working with non academic collaborators.

So I’m going to talk through three key themes that resonate strongly within the cultural heritage sector and across digital humanities projects:

- Public engagement & Knowledge Exchange

- Innovation and Experimentation

- Connectivity and Collaboration

As public institutions, museums, libraries and archives have hundreds of years of practice with educating the public about cultures, art, and humanities. While, like universities, museums have at times been challenged by the change from broadcasting education to engaging in dialogue with the public, there are a range of successful models for deep engagement and collaboration with the public that we can learn from.

As public institutions, museums, libraries and archives have hundreds of years of practice with educating the public about cultures, art, and humanities. While, like universities, museums have at times been challenged by the change from broadcasting education to engaging in dialogue with the public, there are a range of successful models for deep engagement and collaboration with the public that we can learn from.

Obviously with the emphasis on the idea of impact in the REF there has been a big shift and it has changed the landscape of research. But public engagement and knowledge exchange shouldn’t just be for ticking boxes and form filling. PE should not be a new and separate activity for humanities researchers, but rather part of research, teaching, learning and knowledge exchange.

Effective public engagement informs research, enhances teaching and learning, and increases our impact on society.

Done right, engagement should be transformative for all sides. According to the National Co-ordinating Centre for Public Engagement, engagement ‘is by definition a two-way process, involving interaction and listening, with the goal of generating mutual benefit.’ So a two-way exchange of ideas, information and insights, but it is acknowledged that there can be many ways in which humanities researchers can interact with the public.

I am a huge advocate of public engagement and knowledge exchange, and I do believe we can learn a lot from museums, libraries and archives about how thinking creatively about academic research can enable us to speak to a wide range of audiences, even when the research subject seems to be quite specialised. I believe that communicating research to a wider audience is neither time-wasting nor trivializing, but can bring benefits to academics and the public alike.

Thinking outside the box, establishing multidisciplinary research teams and international collaborations with the cultural heritage sector outside academia, push the boundaries of existing technologies and methodologies. Creating an environment which is open to experimentation and innovation.

Thinking outside the box, establishing multidisciplinary research teams and international collaborations with the cultural heritage sector outside academia, push the boundaries of existing technologies and methodologies. Creating an environment which is open to experimentation and innovation.

Museums, libraries and archives have made great efforts to support new research into digital technologies that seek to change the way audiences engage with material culture and heritage. Each of the projects I have mentioned demonstrates how cultural organisations been up for innovation and experimentation and beginning to bridge the divide between research and innovation that has public impact.

Innovation and experimentation are closely related to Risk. Innovation and experimentation in museums, libraries and archives has been a growing topic of conversation of late, and an increasing number of organisations have gone down the path of taking risks and developing new kinds of projects that push the boundaries. A certain amount of risk is always associated with digital projects because they are ‘new,’ ‘innovative’ and ‘cool,’ but there are uncertainties about how much risk is too much risk. How far can the boundaries be pushed with one project and how much tolerance does the institution have? These are questions that many are now facing and questions which many digital humanists are trying to tackle.

Creating a culture in academia that embraces risk is a prerequisite to allow significant innovation to take hold. Digital Museums, Libraries and Archives projects are pushing the boundaries by Recognising that by attempting innovation you expose yourself to risk. The freedom to innovate can only happen when researchers remove the stigma of failure from the process. Instead, celebrate failure as a badge of honour and a key component needed to break old models and embrace innovation.

Ultimately, this presentation proposes that there is a need for collaboration between memory institutions and digital humanities, and that the role of the digital humanities researcher is evolving in order to effectively integrate memory institutions and the public as a partner in future scholarship.

Ultimately, this presentation proposes that there is a need for collaboration between memory institutions and digital humanities, and that the role of the digital humanities researcher is evolving in order to effectively integrate memory institutions and the public as a partner in future scholarship.

There is an dominate stereotypical image of a lone scholar in humanities research surrounded by books (not people), with an inability to communicate with the wider world, a certain amount of reservedness and inwardness. There is a strong association with isolation. But we all know that it is the productive conversations with one another that makes research interesting. But there is still a dominance of the long scholar which it seems important to me to challenge and to question.

Whereas the digital humanities tend to be much more collaborative.

Collaboration is widely considered to be both synonymous with and essential to Digital Humanities. This is because one person can rarely possess all of the (inter)disciplinary and technical knowledge needed to implement many DH projects. Infact, one of the earliest documented examples of a Digital Humanities project, Fr Roberto Busa’s Index Thomisticus (a project started in 1946), was underpinned by a wide-ranging collaboration, not only with IBM, but also including, at one point, a team of 60 who worked directly on the project.

Why do digital humanities scholars collaborate more frequently than ―traditional humanities scholars? What difference does collaboration make?

A survey (by Lynne Siemens at UVIC published in 2011) of digital humanities research teams found that the most common reasons researchers cited for working together are ―Team members have different skill sets and Collaboration is more productive than individual work.

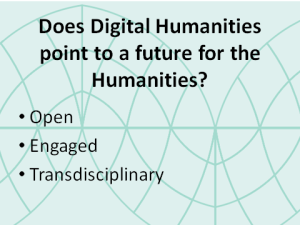

Perhaps the digital humanities point to a future for the humanities in general to be more open, engaged, and transdisciplinary. We all are facing the data deluge, and all are part of a knowledge society that is transitioning rapidly to the digital. It’s important to try to addresses how modes of knowledge production and dissemination are changing as information becomes digitally networked -humanities scholars have to envision new ways of doing their work.

In some respects digital humanities scholars are at the leading edge of a transformation that will affect everyone, but ultimately I believe that the digital humanities will simply become the humanities. Its been argued by some digital humanitsts that the digital humanities should not be about the digital at all. Its all about innovation and disruption. “The digital humanities is really an insurgent humanities” (Mark Sample)

Most of the research sources will be digital, as will the publishing environments. Scholars will need to devise methods to harness abundant information, explore new questions, and represent their ideas in new ways. In the face of skepticism of the value of the humanities, many digital humanities projects working with cultural organisations demonstrate how the humanities can be more interactive, interdisciplinary, and engaged, enabling scholars and the public alike to create and share knowledge.

The main argument being put forward is that humanities researchers should embrace the opportunity to learn from and work with cultural organisations and digital humanists to form a connection between academia and the public.

We need to think less about completed projects and more about work in process, iterative runs and learning from failure; think less about individual authorship and more about collaboration; think less about ownership, authorship and authority and more about sharing and co-creation, and think less about broadcast and more about dialogue.

It is my hope that the reflections in this presentation will help to stimulate dialogue, and suggest future directions for a conversation about public engagement, cultural heritage, and arts and humanities research. This conversation is more pressing than ever, but must continue to welcome new, more diverse and at times discordant voices to the table.

On Monday 22nd June, 2015, I had the pleasure of taking part in The Durham

On Monday 22nd June, 2015, I had the pleasure of taking part in The Durham

Digital Humanities? What on earth is it? Tools for research? cultural expectations? understanding pervasive technology in society? We asked the Northern Bridge doctoral candidates to define and discuss.

Digital Humanities? What on earth is it? Tools for research? cultural expectations? understanding pervasive technology in society? We asked the Northern Bridge doctoral candidates to define and discuss.